Learning from GM 101

Abstract

This report summarizes results reported by participants in the “GM 101 Adventure Design & Game Running” workshop sponsored by Bringing Fire at Gen Con 2023, comprising four individual four-hour sessions intended to introduce participants to the art of game mastering (GMing) a tabletop role-playing game (TRPG). We examined 64 pre- and post-session self-assessment surveys and found that a clear majority indicated greater knowledge of and confidence in their GM abilities and knowledge as a result, specifically reporting improvement in knowing how to create engaging play sessions (95%), respond to what players do during a game (88%), create story through role-playing (84%), and to a lesser extent organize their game ideas (70%). We also found that the participants who were most engaged by the workshop were those who initially reported lower levels of confidence in their GMing; these participants also showed the largest gains in responding to what players do in play.

Introduction

The presence of a Game Master, or GM, in tabletop role-playing games (TRPGs) as the impresario of the game as social event and the auteur of the fiction the game produces, is often taken as a defining feature of the TRPG (see, e.g., Zagal & Deterding 2018, p. 31), even though advocacy for GMless forms in some quarters (Boss 2006) has taken place from the earliest days of the hobby (Peterson 2022). Acting as a GM has typically been construed as a challenging task requiring a wide array of skills and a high degree of dedication to the hobby (see, e.g., Gygax 1987, 1989). The emergence of “Actual Play” as a media form allowing viewers to watch talented voice actors playing out TRPG sessions may have exacerbated this sense of challenge by presenting role-playing in a mediated space that foregrounds the authority of the Game Master (Hope 2017, pp. 31-32) rather than emphasizing how play requires, minimally, the acquiescence of players to that authority (Fine 1983) and more to the point the skillfully collaborative interaction of everyone at the table (Mackay 2001). The increasing number of paid GMs and professional GM services also produces higher expectations about the level at which even amateur GMs should perform (Kinney 2017).

Arguably, these factors detract from the potential strength of fantasy role-playing games as a kind of participatory culture with “low barriers to artistic expression and civic engagement, strong support for creating and sharing creations, and some form of informal mentorship whereby experienced participants pass along knowledge to novices” (Jenkins 2009). And, in fact, reports have been circulating about a “GM shortage,” particularly for Dungeons & Dragons 5th edition, in the face of the rising popularity of the game (Marks 2023).

Thus, while GM advice proliferates over social media and hobbyist publications, these circulations fall short of the kind of mentorship that is characteristic of sustained participatory cultures. We sought to explore whether we could teach GMing in a hands-on fashion such that novice GMs would feel they had improved in their skill as well as knowledge of GMing. Self-assessments by participants in four-hour “GM 101” workshops held at a major North American gaming convention in the summer of 2023 indicate strong increases in confidence and skill.

Theory

Reluctance to run games even in the face of a desire to be a GM amounts to a kind of communication apprehension (CA), understood as an individual’s “fear or anxiety associated with either real or anticipated communication with another person or persons” (McCroskey 1984). Treatment approaches to CA include systematic desensitization, cognitive restructuring, and success visualization training, but such approaches presume that apprehensive persons already possess the necessary abilities for their intended communication task and are simply prevented from employing them by innate personality traits or situational factors. In contrast, skills training or “rhetoritherapeutic” approaches (Phillips 1977) resist the pathologization of CA and seek to inculcate the requisite cognitive skills and interpersonal competencies. In other words, such approaches assume that it is reasonable to be apprehensive until one has adequately prepared for a given communication task.

The range of tasks that a TRPG GM performs as well as the bewildering array of existing GM advice, GM tools and shortcuts, and Actual Play streams, videos, and podcasts makes it difficult for a would-be GM to see their route toward successful practice and increased expertise. The best practice is to actually run a game, but this sort of bootstrapped on-the-job training is less practicable than it once was as performance expectations for GMs from players have increased for the reasons suggested above. In other words, it has become more difficult to develop the shared repertoire that defines game masters as a community of practice (Wenger 1999).

Thus, we designed a hands-on workshop that would let participants practice being the GM at a table of fellow participants. The workshop consisted of two main exercises. Dungeonstorming, the first exercise, derives its name from a portmanteau of “dungeoncrawling” and “brainstorming”; that is, preparing a dungeon adventure via a brainstorming exercise. To facilitate that exercise, we borrowed Burneko’s (n.d.) sequence of questions for treating a role-playing game location (i.e., a dungeon) as a narrative framework. We envisioned that participants would work in small groups to answer those questions and thus create a shared framework to draw upon during the second exercise, the GM Hot Seat. We devised a simple rubric to teach GMing practice (see Figure 1, The GM “Hot Seat”). Once we moved into the GM Hot Seat exercise, participants would rotate through the GM position and lead the others through their collaboratively created dungeon in turn.

We created a simple TRPG system that we called “Roll Some D20s” (RSD) that while relatively rules-light would seem relatively intuitive to those familiar with D&D-type mechanics (i.e., roll a twenty-sided die, higher results produce better outcomes). These mechanics were situated within a rules framework intended to call attention to the dynamics of play at the table. When not serving in the GM chair, participants played fantasy role-playing characters described by an adjective and a noun (”brave warrior,” “clumsy thief,” “arrogant wizard,” and so forth being played by players of particular types (”Combat Monster,” “Thespian,” “Problem Solver,” for example). The player type chosen by the participant determined what sort of in-game action gave them experience points (XP) to level up their character, so that a Combat Monster received XP for defeating monsters, a Thespian for speaking and being answered in character, and a Problem Solver for identifying challenges and coming up with solutions.

The GM during a given portion of the exercise, in contrast, would receive XP for employing GM Techniques keyed to the Describe-Listen-Judge rubric. In this way, their attention would be directed both to the fundamental elements of the process and the possible variations in how to implement the fundamentals.

Method

We made an event called GM 101 Adventure Design & Game Running available as a workshop for 30 people four times on the Gen Con 2023 schedule, describing it as “a hands-on coaching session for new and aspiring GMs to gain experience with adventure prep and session-running techniques. By the end, you’ll have run a game session and be ready for more!” We submitted an additional “long description” to the Gen Con event catalog providing this information:

You want to run a game—but don't think you're ready. Or maybe you’re looking to polish your GM skills. This workshop is made specifically for you! Together, we’ll “dungeonstorm” a short adventure scenario. Then you’ll take turns in the GM chair while others play-act as your adventurers. Just as in real life, your players will have their own play styles and preferences that you’ll have to incorporate into the overall group dynamic. We’ll coach you so everyone can have a fun and engaging game—including you. You’ll leave this workshop with a range of approaches and tools you can bring straight back to your own table along with the confidence to run more games, hone your skills, and become an awesome GM!

We recruited experienced GMs as “GM coaches” to help facilitate the workshop and trained them on the Dungeonstorming and GM Hot Seat exercises in a single hour-long training session intended to familiarize them with the basic elements of the workshop.

We made an intake survey available to convention-goers when they registered for our event, and sent follow-up messages in the weeks prior to Gen Con to encourage registrants to complete the intake survey. This consisted generally of qualitative, open-ended questions about their GM experience, any plans for future games, and understanding of the GM role. But we also asked them to rate their “level of experience” as both a GM and as a player on a scale from 1 to 5. We received 29 responses from registrants to GM 101.

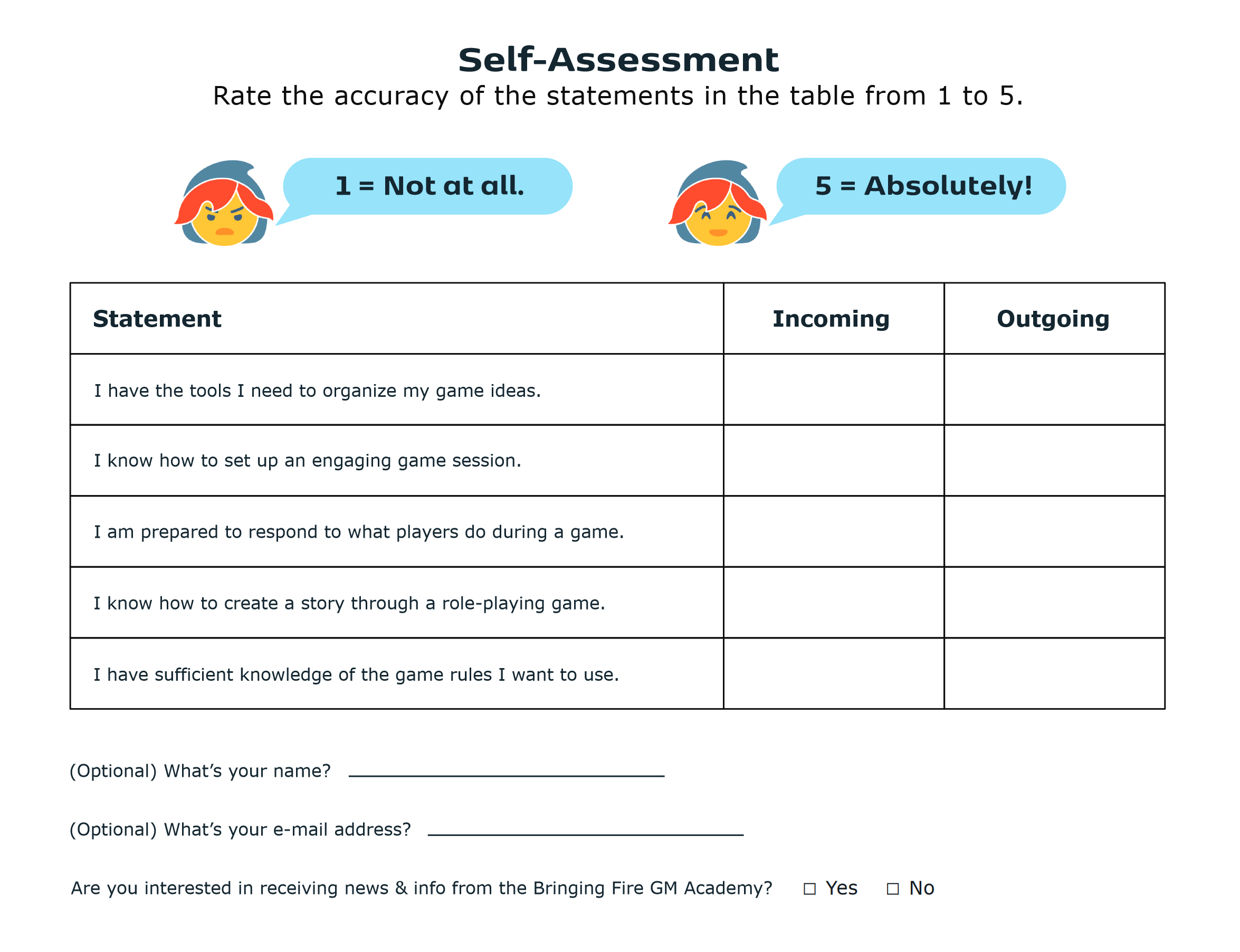

We ran 4 sessions of between 16 and 24 participants each, with a total of 73 participants across the four sessions out of a total of 91 registrants (i.e., ticket holders). At the beginning of each session, we asked participants to rate their agreement with each of five statements about their GM abilities on a five-point LIkert-type scale ranging from “not at all” to “absolutely” (see Figure 2, “Self-Assessment). At the end of each session, we asked them to answer those questions again, and conducted a 15 to 20 minute debriefing with participants.

We collected 64 completed self-assessment forms from participants, a completion rate of about 88%. We suspect that some participants held onto the form despite our urging because it contained workshop content they wished to retain on the obverse side.

Findings

We expected that our description of the workshop would attract novice GMs, and this was generally true. Of the 29 intake forms, fully half (52%) reported their GM Experience level as 1 (the median and mode), with a mean of 2 (sd 1.1).

The ages of intake survey respondents ranged from 13 to 55, with a mean of 33.9 (median 32, sd 10.3). More than half (55%) identified their gender as male, about a quarter (24%) as female, and the remaining six individuals as gender non-conforming in some way. They were almost entirely white, with 26 identifying their ethnicity as some variation upon Caucasian, northwestern European, or white. One respondent self-identified as Black; another, as Latino. The remaining respondent didn’t answer.

Respondents expressed a wide array of concerns they hoped the workshop would address, including developing improvisational and storytelling skills, making game sessions in general and combat scenes in particular more interesting, avoiding “railroading” (depriving players of real in-game choices), being more organized, gaining familiarity with the rules, and even getting better at voice acting.

Debriefing comments were highly positive at the end of each session. “I’m better than I thought I was,” said one participant, to applause from the rest of the room. Other people talked about realizing how to be more flexible and responsive in the moment to what players did. “I felt more confident in how to respond to what my players were doing in the game,” someone told us. “For example, if they had a really bad roll, what's the consequence of that roll? Or if they did really well, what rewards or benefits should they get?”

Participants also pointed to the value of the techniques that the workshop employed. “I found Describe Listen Judge to be very helpful,” another participant said, referring to our mnemonic for the fundamentals of the GM process. Others thought that the collaborative approach of the workshop had applications that they could adopt at their own tables. “I've always kind of had this idea that...if somebody pokes the corners of the world, it has to be seamless,” one attendee explained. But the act of of immediately taking over from another GM helped him “get over [that] and get in the mindset that it can be kind of on the fly ad hoc and nobody's going to be, you know, upset. They're going to help.” The insight that not everything needs to be mapped out “super perfect” and accounted for “before you can even sit down” was for him an important realization. Additionally, some found that using the Roll Some D20s (RSD) system as the dice mechanic for the game they played in the workshop made them more open to using rules-light approaches that they had previously found daunting.

Table 1 compares the self-assessment scores reported at the beginning and end of each session.

Table 1. GM Self-Assessment Results

Note. All differences significant at the p<.01 level

For all five items the increase in the average self-assessment response was statistically significant when examined via paired-samples t-test even when the significance threshold was raised to discount multiple comparisons.

We thus looked at the self-assessment more conservatively by looking for reports of improvement in any of the items, and found that clear majorities saw themselves improving in every item except for rules knowledge. Table 2 provides the details of this tabulation.

Table 2. GM 101 Improvement

We also asked participants if they were interested in receiving news and information from the sponsoring organization’s “GM Academy,” which we took as a measure of engagement with the workshop. Of the 64 completed responses, 45 said yes while only 19 said no. These engaged participants seemed to be initially less experienced or less confident than the non-engaged participants, with significantly lower incoming self-assessments, t(62)=1.9, p<.05. However, the engaged participants reported greater improvement in responding to players, t(62)=2.1, p<.05.

Discussion

Each of the self-assessment items was linked to a particular concern that had been expressed on the intake forms. We included items in the self-assessment that we thought would show little to no improvement as a way of detecting potential response bias from participants.

And while some of the results we saw did suggest a positive response bias, the comments that one workshop participant left in the margins of their self-assessment form about what they’d learned in each category suggested that at least some participants carefully evaluated each item. “No tools learned for organization,” this participant wrote to explain the lack of movement for that item, a 3 both before and after. They added that the exercise did “help prep ideas” and that they “loved dungeon storming questions,” suggesting that the adventure design process could potentially be seen as at least tangentially related to organization. And in terms of rules knowledge, the gain they associated with that item was learning to make “better use of ‘fast forward’ to skip boring sections [and to] just make a decision.” This suggests that thinking about the procedures of play—knowing which rules to use when—as part of an individual GM’s rules mastery is a potentially useful insight.

The case of organization is really interesting, occupying as it does a middle ground between the high-impact self-assessment categories and rules knowledge, upon which the workshop by design had little impact. The pattern of response for organization more closely resembles the former items than the latter. The implication is that, even without our intending it, participants understood some of the adventure design techniques we shared with them as tools for organizing their ideas in a way that was useful to them.

But the striking result is how clearly and strongly learning how to create engaging sessions at the table emerges as a benefit of participating in GM 101. Responding to players and creating story through role-playing also show up as benefits, as we had intended. The fact that a majority of participants reported no improvement in their rules knowledge as a result of attending our system-agnostic workshop adds credibility to the other results, even in the face of the demand characteristics of the self-assessment. Additionally, the link between improvement in responsiveness to players and engagement with the workshop points to its potential value in fostering a participatory culture in the TRPG scene as well as a specific community of practice (Wenger 1999) organized around the application and elaboration of GM 101 techniques.

Conclusion

GM 101 shows an immense amount of promise as a tool for helping aspiring GMs develop their craft in a way that highlights the particularly interactive character of tabletop RPGs as an expressive form and develops the participatory features of the TRPG cultural scene. To the extent that teaching people how to GM can serve as a formative event in the initiation of a larger community of practice (Wenger 1999), this workshop will have value beyond its immediate skill-building function.

References

Boss, Emily Care. “Collaborative Role-Playing: Reframing the Game.” Push, no. 1: 13–36 (2006) [online]. Available at http://www.jwalton.media/#/push/. Accessed August 4, 2022.

Burneko, Jesse. Dungeons & Dilemmas: The Dungeon as Narrative Framework and Encounters as Moral Puzzles [zine]. Bloodthorn Press, n.d.

Fine, Gary Alan. Shared Fantasy. University of Chicago Press, 1983

Gygax, E. Gary. Role-Playing Mastery. Perigee Books, 1987.

Gygax, E. Gary. Master of the Game. Perigee Books, 1989.

Hope, Robyn. “Play, Performance, and Participation: Boundary Negotiation and Critical Role.” Masters Thesis, Concordia University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, 2017.

Jenkins, Henry. Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century. MIT Press, 2009.

Kinney, Asa. “Pay to Play RPG Paid GMs: Are You Worth It?” Nerdarchy, September 19, 2017 [blog]. Available at https://nerdarchy.com/are-you-worth-it-pay-to-play-game-masters/. Accessed August 30, 2023.

Marks, Aaron. “What GMs Want.” Cannibal Halfling Gaming, August 23, 2023 [blog]. Available at https://cannibalhalflinggaming.com/2023/08/23/what-gms-want/. Accessed August 30, 2023.

McCroskey, James A. “The Communication Apprehension Perspective.” In Avoiding Communication, edited by J.A. Daly and J.C. McCroskey (pp. 13-38). Sage, 1984.

Peterson, Jon. The Elusive Shift. MIT Press, 2022.

Phillips, Gerald M. “Rhetoritherapy Versus the Medical Model: Dealing with Reticence.” Communication Education, vol. 26, no. 1: 34-43 (1977).

Wenger, Etienne. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Zagal, Jose P., and Sebastian Deterding. “Definitions of ‘Role-Playing Games.’” In Role-Playing Game Studies: Transmedia Foundations, edited by Sebastian Deterding and Jose P. Zagal (pp. 19-52). Routledge, 2018.